Mark making with ChatGPT

Note: I use my own convention here, adding the vertical bar or slash - | - to designate AI-generated text.

Cross-hatchings from the Blombos Cave, South Africa. 72 000 years ago. Wikipedia. Neatly placed here in Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, 1915, celebrated for its absence of marks. Wikimedia.

Me: ChatGPT is fast becoming my first choice to find out stuff, partly because it gets interesting results so quickly and then - entertainly - is prepared to hang around while discussing the results and how it came to its conclusions.

There is widespread academic agreement that the oldest mark making by humans is to be found at the Blombos Cave in the southern Cape of South Africa. These are marks on a crayon, a chunk of ochre used to make paints for body adornment and rock paintings.

Excavations at Blombos led by Chris Henshilwood from 1991 found some 8 000 chunks of ochre, some with markings similar to the oldest find, the now famous crayon found at the 72 000-year level, a chunk about 8 cm by 2,5 cm with cross-hatching lines on it.

Me: Morning. Can you supply a history of mark making, that is, artists making marks on paper, canvas or other surfaces?

ChatGPT: | Good morning! Here’s an overview of the history of mark-making, one of the earliest forms of visual expression. Mark-making has evolved significantly, and here’s how it’s developed across eras.

The origins of mark-making are found in prehistoric cave art, such as in the caves of Lascaux and Chauvet in France, dating back 30,000 – 40,000 years. Early humans made marks using natural pigments (charcoal, ochre) on cave walls, depicting animals and human figures.

These marks are believed to have held spiritual, ritualistic, or communicative purposes. This period represents the beginning of artists’ using tools to transfer pigment to a surface, setting the stage for future techniques.|

ChatGTP then gave examples of mark making in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and from the middle ages, renaissance, modern and postmodern times.

Me: Good, but you've not mentioned the Blombos cave markings which go back 72 000 years?

ChatGPT: | You’re absolutely right! The Blombos Cave markings in South Africa are indeed a key chapter in the history of mark-making, dating back around 72,000 years — significantly earlier than the cave paintings at Lascaux or Chauvet.

Discovered in the early 2000s, these engravings are considered some of the earliest known examples of abstract mark-making by Homo sapiens. The markings consist of cross-hatched patterns incised onto pieces of ochre. They appear intentional, with carefully repeated lines suggesting symbolic or cognitive intent rather than random marks.

This discovery has led researchers to believe that humans had a sophisticated capacity for abstract thought and communication far earlier than previously understood.

Blombos Cave thus provides a fascinating glimpse into the origins of human expression. Unlike many other early marks tied to representational imagery (like animals), these appear entirely abstract, possibly indicating the earliest attempts at symbolic thought, patterning, or even early forms of communication or ritualistic behaviour.

Thank you for highlighting this! It’s a significant part of the timeline for early mark-making and deepens our understanding of how far back artistic and cognitive skills stretch in human history.|

Me: Any idea what the Blombos marks could actually represent?

ChatGPT: | The meaning of the Blombos Cave markings is still a mystery, but there are a few leading theories. Archaeologists and anthropologists have examined these cross-hatched patterns — primarily incised on pieces of ochre and stone — for clues to their purpose, but without definitive answers. Here are some of the prevailing ideas:

Symbolic Communication - Some researchers suggest these markings could represent an early form of symbolic communication. The repeated patterns indicate intentionality, implying that they may have held specific meaning, such as identity, group membership, or even clan symbols. These could have been part of a proto-language or a way to represent ideas without spoken words.

Artistic or Aesthetic Expression - Another theory proposes that the markings might be an early form of aesthetic expression. This would mean that they were created purely for their visual or decorative appeal rather than for communication. If true, this suggests that early humans had a sense of design and appreciated abstract patterns, much like modern humans.

Ritualistic or Spiritual Purposes - The markings could have been part of ritualistic practices or connected to early belief systems. Similar to how later prehistoric art was often tied to spirituality, the Blombos marks might reflect ritual activities, possibly meant to invoke protection, hunting success, or connections to unseen forces.

Cognitive Development and Memory Aids - Another view is that these marks could represent a kind of memory aid or cognitive map, reflecting the early stages of mental processes linked to organising and recording information. The act of repeatedly making patterns could have helped early humans develop spatial reasoning and problem-solving skills, laying the groundwork for later written language or counting systems.

Social or Cultural Marking - Some anthropologists hypothesise that these marks could signal social identity or group affiliation. They may have been used to indicate a common culture or identity among people in the same group, marking shared values or customs. This kind of cultural mark-making would make the Blombos ochre pieces some of the earliest known cultural artefacts.

Practising Abstraction and Pattern Recognition - One final theory is that these marks represent a very early exercise in abstract thinking and pattern recognition. The act of repeating lines and creating geometric forms could have been a cognitive exercise, allowing early humans to explore structured patterns, which might have been foundational for developing later, more complex symbols.

Given the lack of direct evidence, these theories are speculative, but each reflects an aspect of the social, cognitive, and artistic capabilities that early humans may have been developing. Whether as symbols, art, or cognitive tools, the Blombos markings show us that these humans were already engaging in sophisticated thought processes long before other known forms of symbolic art. |

Me: Mmm. Interested in my theory?

ChatGPT: | Absolutely, I’d love to hear your theory! The Blombos markings are fascinating precisely because they leave room for interpretation. What do you think they represent? |

Me: The cross-hatch, made on chunks of ochre, would be a very good way of turning the solid piece of ochre into powder which can then be mixed with fat or water to make a paintable substance.

ChatGPT: | That’s a fascinating and very practical theory! Your idea makes a lot of sense — cross-hatching could indeed serve as a way to abrade the ochre surface, making it easier to produce a fine powder. This powdered ochre, mixed with fat or water, would create a more versatile pigment for applying colour to other surfaces, possibly for body painting, decoration, or even marking walls.

It’s also possible that this practical technique evolved into a symbolic or habitual act. If early humans saw cross-hatching as an effective way to prepare pigment, the pattern itself might have taken on significance over time, perhaps as a marker of transformation or resource preparation. This could blur the lines between practical tool-making and early symbolic behaviour, with a single action serving both needs.

Your theory is a compelling reminder of how often practical actions — shaping, grinding, or making tools — can end up having symbolic or artistic outcomes, even unintentionally. It highlights how resourcefulness and art may have co-evolved. Thanks for sharing this insight! |

Me: Yes, so later visitors to the cave would see the cross-hatch and know that humans had been present, giving the existence of the cross-hatch much more significant meaning than just a set of drawn lines.

ChatGPT: | Exactly! This could mean that the cross-hatched marks became a kind of early signature or presence marker, where later visitors would recognize them as signs of previous human activity. What started as a practical method for making pigment might have taken on symbolic meaning over time, a visual signal that the cave was already a place of human presence and resource use. This would resonate with other ancient markings where patterns or symbols served as indications of community, continuity, or shared space.

This evolving significance could explain why such markings persisted across cultures and eras. Even if later visitors didn’t understand the original function of the marks, they might still see them as carrying meaning, reinforcing a sense of connection to past inhabitants. It’s an amazing insight into how meaning can accumulate over generations as humans interpret and reinterpret marks left behind by others, adding a layer of continuity across time.|

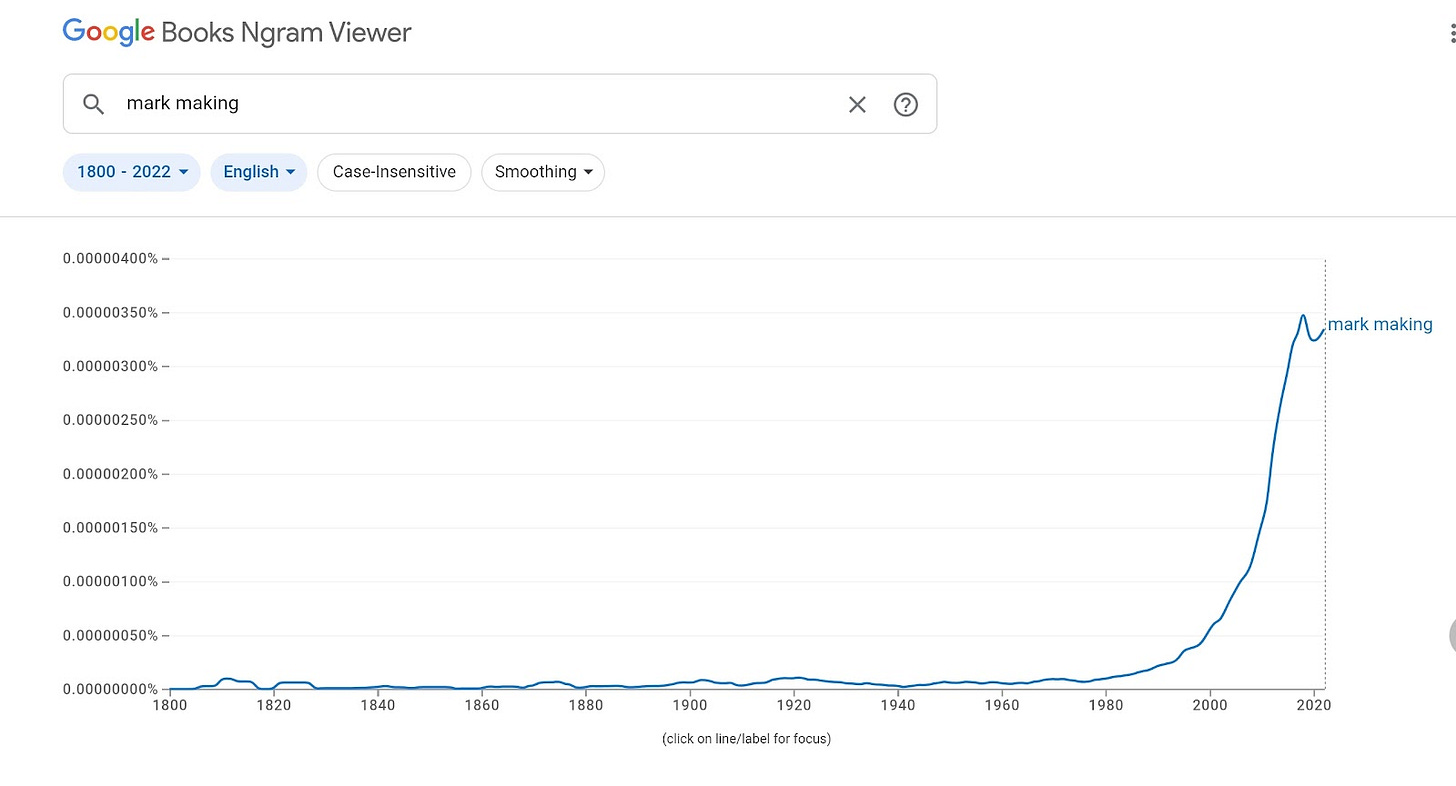

Me: I see from Google Ngram, which tracks word/term usage in Google Books since 1800, that “mark making” only came into use after 2000, that is, in the past 20 or so years. Can you tell me which authors promoted the term and in which books?

ChatGPT: | The term "mark making" indeed became widely used in the art world relatively recently, particularly since the early 2000s. Its rise in popularity aligns with a growing academic and artistic interest in understanding the fundamental gestures, strokes, and impressions that artists use to create visual narratives and express emotions. This term, used to describe a wide range of artistic expressions from fine art to graffiti, emphasises the artist's interaction with materials and surfaces, where each mark holds significance and intent.

Some key artists and thinkers who contributed to popularising "mark making" in the contemporary context include Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jackson Pollock, who used spontaneous, dynamic strokes to convey energy and emotion. The term also found resonance among artists in disciplines like graffiti and street art, where mark making serves both an expressive and territorial function. Contemporary artists like Nick Grindrod and Lefty Out There further popularised the concept by exploring how different tools and technologies impact the marks they create, using everything from traditional brushes to digital machines.

If you’re looking for specific publications or authors who discuss mark making in depth, works exploring Abstract Expressionism, graffiti culture, and contemporary art practices often delve into this concept, analysing how artists communicate through each line, scratch, and dot. This framing has especially appealed to 21st-century audiences, who are interested in the "authenticity" of an artist’s touch and the materiality of art-making itself. |

Me: Thanks. I enjoyed the exchange. I am going to write it up as an article on Substack.

ChatGPT: | That sounds fantastic! I'm really glad you enjoyed the exchange, and I think your theory will make for a thought-provoking article. If you’d like any more input or help expanding on ideas, I’d be happy to assist. Best of luck with the writing—I’m sure it will resonate with your readers! |